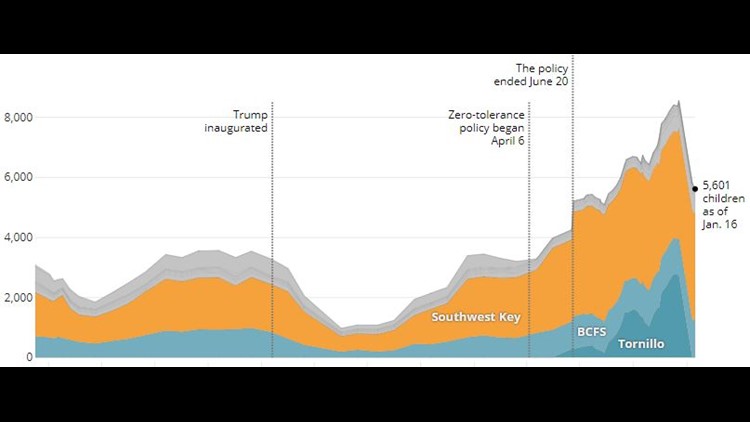

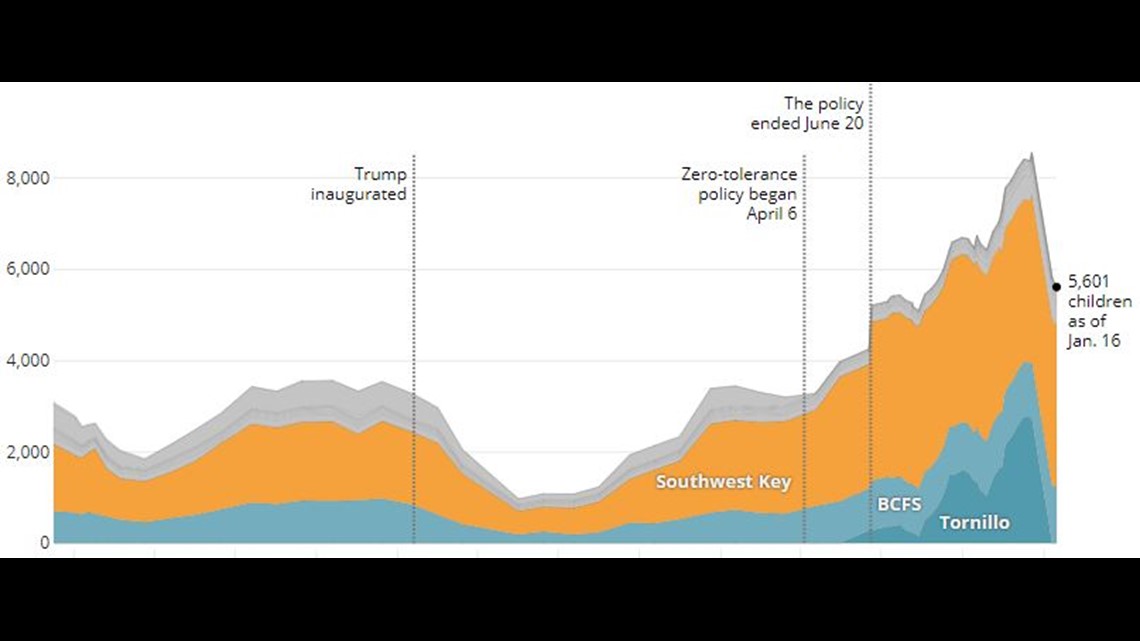

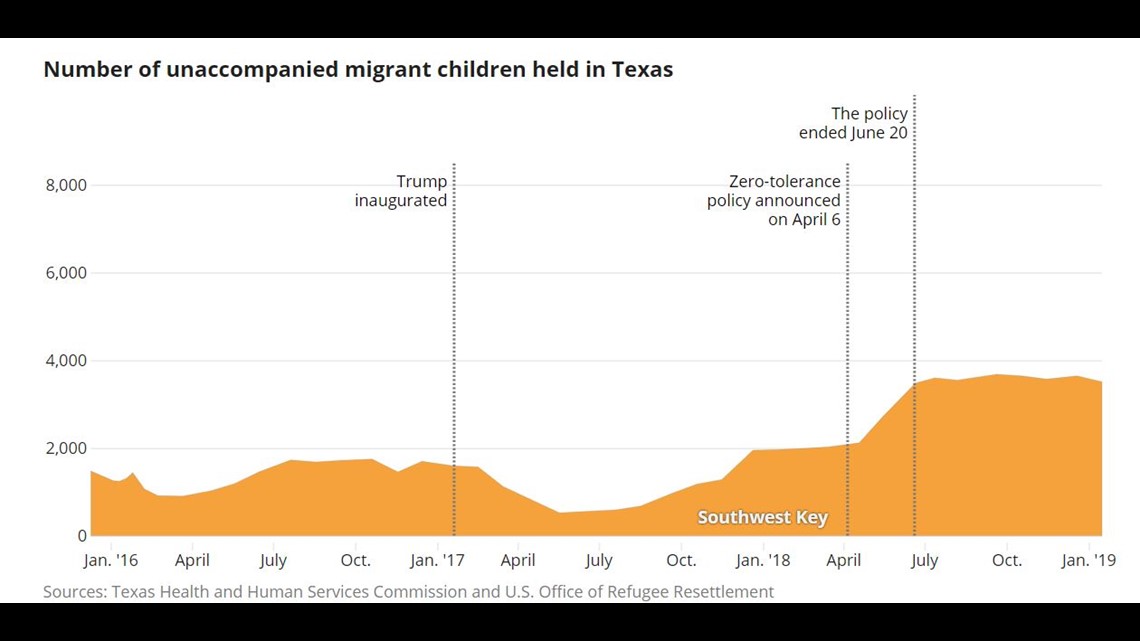

Number of unaccompanied migrant children held in Texas

- Sources: Texas Health and Human Services Commission and U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement

In Texas, and nationally, the number of unaccompanied migrant children being held in government-funded shelters declined in January, according to the latest state and federal data.

Most of the drop can be attributed to the closure on Jan. 11 of a temporary tent shelter in Tornillo, near El Paso. However, the Trump administration also announced in late December it would relax screening policies that immigrants rights groups have blasted for slowing placement of migrant kids with relatives and other sponsors.

As of Jan. 16, state data show there were 5,601 children living at the 34 remaining shelters across the state for unaccompanied youth.

That’s compared to 8,549 children who lived in those shelters, and Tornillo, on Dec. 19 — a decline of 34 percent.

Nationwide in January, there were at least 10,000 children being held in federal shelters, according to data from the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement. That means about 56 percent of all institutionalized minors are living in Texas. A month ago, there were more than 14,300 kids in shelters nationwide.

Less than a month ago, there were more than 2,700 children living at the Tornillo shelter — a hastily built tent city near El Paso that was originally designed to house 360 children when it opened in June. That facility, a federal installation overseen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and run by a contractor, was not regulated by the state.

It was unclear exactly how many children were living at Tornillo until an Associated Press investigation in December detailed more complete data about all minors in the custody of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement.

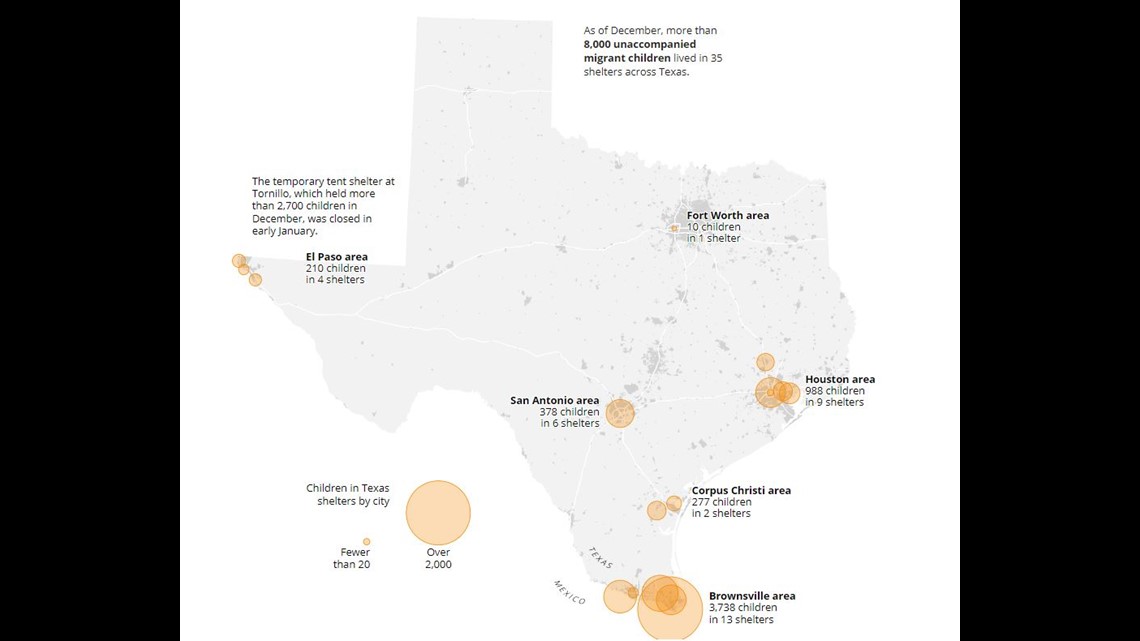

As of December, more than 8,000 unaccompanied migrant children lived in 35 shelters across Texas.

- Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission and U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement

Shelters are meant to serve as a temporary home for children after they arrive in the U.S., typically without an adult, before they can be placed with U.S.-based sponsors — typically family or friends. Despite the recent decrease, the number of children being held in shelters across the country has increased dramatically since last summer. It’s unclear how much of the surge can be attributed to a greater number of unaccompanied children arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border, and how much is the result of federal policies that have slowed the rate at which children are paired with sponsors.

According to the federal government, some of the children have been released sooner than anticipated because, in late December, the administration ended a portion of its strict screening policies that had slowed the placement of migrant kids with relatives.

On Dec. 19, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said the Office of Refugee Resettlement would still fingerprint sponsors and cross-check their information with FBI national criminal history, state repository records and U.S. Department of Homeland Security arrest records. But it said it would stop doing such extensive background checks on other members of the household.

Throughout 2018, detention shelters asked regulators for permission to add more beds as the number of children in their care ballooned. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission decides whether shelters get a capacity variance, which allows them to house more children.

As of Jan. 16, Texas’ 34 state-licensed shelters had permission to accommodate up to 6,289 children, according to the health commission. With 5,601 kids living in them, that means they’re at 89-percent capacity.

Those shelters, licensed as child care providers, have a long history of regulatory inspections that have uncovered serious health and safety deficiencies.

A Texas Tribune review of state records found that, over the last three years, inspectors have discovered 468 health and safety violations at the facilities, which can each house anywhere from 20 to more than 1,400 children at a time.

The facilities are required to provide basic care to the children of detained migrants, including medical care and at least six hours of daily schooling. Their inspection reports, though often light on details, paint a picture of the abuses that young children may face in a foreign environment where many face language barriers and a history of trauma from the journey to the U.S.

Counts of children on this page are current as of January 2019, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission and U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement.

Southwest Key Programs, the private contractor operating a converted Walmart in Brownsville as a shelter for more than 1,500 children, is the largest operation in Texas authorized to take in children separated from their parents. Founded in 1987, the nonprofit says its mission is to “provide quality education, safe shelter and alternatives to incarceration for thousands of youth each day.”

Inspectors found more than 200 violations at the group’s 16 facilities in the last three years, records show. On Oct. 11, 2017, at a Southwest Key facility in San Benito, an employee appeared drunk when he showed up to work. A drug test later found the employee was over the legal alcohol limit to drive. Inspectors also found shampoo dispensers filled with hand sanitizer and bananas that had turned black. In two instances, children were made to wait before receiving medical care: three days for a child with a broken wrist, and two weeks for a child with a sexually transmitted disease.

A spokesman for Southwest Key said the organization had worked to correct the problems identified by regulators. Of the list of violations, spokesman Jeff Eller said: “While it’s not inaccurate, it’s grossly unfair to say that without acknowledging that we acknowledged our mistakes and made immediate corrections.”

At a Harlingen facility owned by BCFS, employees were alleged to have struck up “inappropriate relationships” with children in their care. Children complained of raw and undercooked food, and one child in late 2016 suffered an allergic reaction after a staff member gave the child a snack.

In April at another BCFS facility in San Antonio, a staff member helped arrange for a child’s family member to send the child money — but when the cash arrived, the staff member kept it. The year before, an employee gave children “inappropriate magazine pages” that depicted naked women, while a few months before, staff members were found to have failed to supervise their wards closely enough to prevent one child from “inappropriately” touching two others.

Comprehensive Health Services

A group called CHSI applied in August to open three new shelters — two in San Benito and one in Los Fresnos — to care for unaccompanied boys and girls up to 17 years old or as young as infants, documents show. The name refers to Comprehensive Health Services, a Florida-based company that has previously received contracts from the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement.

Their three shelters opened in late September or early August and have a combined capacity of 610.

Upbring

Federal funding received from 2016-18: $60.7 million

Upbring operates two facilities that accept unaccompanied minors and children separated from their parents by immigration authorities. The company was previously known as Lutheran Social Services of the South.

Catholic Charities

Federal funding received from 2016-18: $21 million

Catholic Charities, which has worked with the federal government to resettle refugees since at least 1983, operates three shelters for unaccompanied children through its branch at the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston.

St. Peter St. Joseph Children's Home

Federal funding received from 2016-18: $23.1 million

St. Peter St. Joseph Children’s Home, which began as an orphanage in 1891, according to its website, operates an emergency shelter in San Antonio with a contract to house unaccompanied migrant children.

Shiloh Treatment Center Inc.

Federal funding received from 2016-18: $17.2 million

Shiloh Treatment Center Inc. was first incorporated in 1995, according to the Houston Chronicle. It first began receiving federal funding to house migrant children in 2013. It has been dogged by allegations of abuse following the 2001 death of 16-year-old Stephanie Duffield at the center after she was restrained by staff, but the treatment center has been found to be in compliance with state requirements. Shiloh did not respond to a request for comment.

Seton Home

Federal funding received from 2016-18: $9.7 million

Seton Home, which opened in 1981, according to its website, operates a facility in San Antonio.